Andrew J. Bacevich, Jr. is an American political scientist specializing in international relations, security studies, American foreign policy, and American diplomatic and military history. He is currently Professor of International Relations and History at Boston University. He is also a retired career officer in the Armor Branch of the United States Army, retiring with the rank of Colonel. Professor Bacevich is author of several books, including American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of US Diplomacy (2002), The New American Militarism: How Americans are Seduced by War (2005) and The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism (2008). He has also appeared on television shows such as The Colbert Report and the Bill Moyers Report and has written op-eds which have appeared in papers such as The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, and Financial Times. He is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

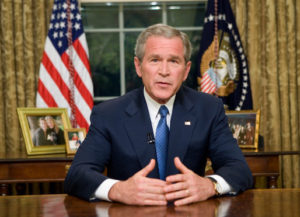

Professor Bacevich has been “a persistent, vocal critic of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, calling the conflict a catastrophic failure.” In March 2007, he described George W. Bush’s endorsement of such “preventive wars” as “immoral, illicit, and imprudent.”

We spoke with Andrew Bacevich earlier.

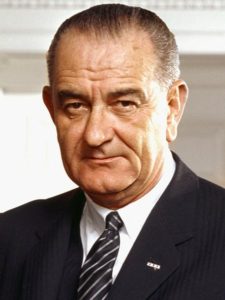

DAVID: Tying sports to war. Lyndon Baines Johnson has been caught on tape saying he didn’t want to be the first US president to lose a war. Americans… and this is, again, this is on sports. We refuse to admit defeat. We love sports. It’s a metaphor for war. And we often think about the win/loss column. Nixon and even George W. Bush wanted to know how many of the other guys were we getting.

So for our sports fans, did we lose Vietnam? Did we lose Iraq? Are we losing in Afghanistan? And would America be better off if we could admit defeat? Is there a benefit to saying we lost? Or does admitting defeat in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, does that dishonor our troops?

President Lyndon Johnson said he didn’t want to go down in history as the first U.S. President to lose a war.

ANDREW BACEVICH: Well, I don’t think it dishonors our troops. I mean, my argument would be that we need to be realistic, pragmatic, and deal with reality. And the reality is… first of all, war is not a sport. War is, as Carl von Clausewitz said, a continuation of politics by other means. It’s using violence in order to achieve political purposes. And we need to be honest enough to recognize that in Vietnam, we failed to achieve our political purposes. In Iraq, we failed to achieve our political purposes. In Afghanistan, in all likelihood, we will fail.

And you face up to that, and you act accordingly. I mean, we need to recognize that the notion that using military power can somehow fix the Middle East in ways that will serve our interest — it is not going to happen. We’ve been trying to do that for 30 years now, and we have met with one failure and frustration after another. And…

DAVID: I’m going to interrupt you. I’m going to interrupt you. You’re a colonel.

ANDREW BACEVICH: Well, I was, long ago.

DAVID: Okay. 25 years in the military. West Point. Vietnam. Does it make you feel uncomfortable to say, “We lost?”

ANDREW BACEVICH: Well, no, it doesn’t. I mean, I’m… and when I was a captain just coming back from Vietnam, I might have had a different view at that time. I was a different person in a different circumstance. But at this stage of my life, I think we do a disservice to our military, and we do a disservice to our country, if we basically lie to ourselves about what our military involvement in recent decades has yielded. I think we owe it to those who served and sacrificed to call a spade a spade.

DAVID: Mm-hmm. Which brings us to more of the sports theme: spectators. War is not a spectator sport. And yet in your book, you kind of say it has become a spectator sport for Americans. We got rid of the draft in 1973, and we’ve converted to an all-volunteer military. And within seven years of that, Ronald Reagan was elected president. For the next 30 years, our political system lay waste to the middle class. Unions. We’ve witnessed unprecedented homelessness and a celebration of excess that would make Caligula cringe.

What toll has this all-volunteer army taken on the common man? On… not the soldier, but on us, the people who don’t volunteer. Who stay home? What’s the toll?

ANDREW BACEVICH: We, the people, forfeited any ownership of our military. It’s not America’s military. It’s Washington’s military. Washington has used that military as it has seen fit, and, I think, with mostly negative consequences. So the militarization of US policy, which had already begun during the Cold War, but which was accelerated by the move to the all-volunteer force and then the end of the Cold War, has not made us more secure. It’s not made us more prosperous. It’s not made us more free. I think that the militarization of policy since the creation of the all-volunteer force has hurt the country, meaning its hurt us.

President George W. Bush, former owner of the Texas Rangers, tried to fight two wars without a draft and by gifting the American people with a series of tax cuts.

DAVID: They ask why is Washington, DC, why are our politicians so out of touch? They have so much contempt for us? I think a lot of that is rooted in the all-volunteer army. It’s gotten easier, if you’re a politician or a bureaucrat in Washington, surrounded by soldiers in Washington, DC, guys who actually volunteer and make a sacrifice. If I were a politician, I would have nothing but contempt for the rest of America, because they don’t make a sacrifice.

And under Bush, W. Bush, he was handing out tax cuts during a time of war.

ANDREW BACEVICH: Right.

DAVID: Now we don’t sacrifice ourselves, our family, or money. Why wouldn’t Washington have nothing but contempt? If I were living in Washington, if I were… I would look at all Americans as welfare cheats.

ANDREW BACEVICH: I’m with you, but I think I’d point my finger at us, at the American people who have allowed this circumstance to develop. We have chosen a definition of citizenship that is paper-thin. And we have not been willing to consider the possibility that citizenship should entail collective obligation. And therefore, to see wars as not simply Washington’s business, but as the people’s business.